epipole whitepaper, written by Sarah Jardine, CEO epipole

July 2024

Sarah Jardine (centre) is the brilliant engineering mind leading epipole into the future

In the beginning…

A long time ago, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, I graduated as a Laser Engineer. I have spent the 30-odd years of my career since then working in manufacturing, the majority of which has been spent working in manufacturing of retinal imaging medical devices.

Over the years I have toured hundreds of Optometrists and Ophthalmologists round my factories, and I have found that just as many want to talk about efficiency and productivity improvements as want to talk about the technology that goes into the retinal imaging devices.

This shouldn’t really be surprising as the fundamental principle of manufacturing is FLOW, and similar strategies can be applied to streamline operations in healthcare settings. By focussing on the seamless progression of patients from check-in to check-out, we can reduce waiting times, enhance the patient experience, and optimise the utilisation of resources.

There is a direct relationship between creating efficiencies and increasing profitability, which results in an increased competitive edge, regardless of the industry you’re working in.

Always Improving

In manufacturing we talk about continuous improvement and lean manufacturing, and these are based on the five lean principles shown in the graphic below:

Identifying value from the customer’s perspective means identifying what the customer is willing to pay for, and the value stream is the complete end-to-end process (both of which will be other white papers on their own), whilst flow describes how patients (or parts in the case of manufacturing) progress through the system.

In the simplest terms, good flow is predictable, and bad flow is start and stop. A key tool for improving flow is waste elimination.

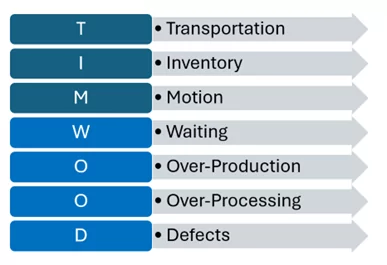

In manufacturing we identify 7 Wastes, and we remember them with the mnemonic TIM WOOD:

It might not be immediately obvious how these manufacturing concepts directly relate to a healthcare environment, but let’s consider waiting, either between tests and procedures, or indeed even before being able to start any tests.

We might also refer to waiting time as a delay, and often we recognise it because “things are getting backed up”, as the impact can have a knock-on effect for the rest of the day.

For example: How often have you been waiting for a patient who doesn’t turn up on time, or for them to complete registration, medical history or insurance forms?

Sometimes we consider making appointment times longer or leaving more time between patients to compensate for these delays, and whilst this can have a positive effect, longer appointments mean that we schedule fewer patients per day, so we are becoming less, not more, productive.

This reduction in productivity is because the solution doesn’t deal with the root cause of the problem, i.e. that the patient is late, or does not turn up at all. Longer appointment times don’t encourage patients to arrive on time, it simply means that the effect of someone being late is reduced.

A Better Way

Instead, we could implement an automated text reminder system that would remind patients of their appointment time and the need to be on time. Such a system would also allow us to advise patients of localised issues such as roadworks, access to parking, etc, enabling them to allow more time for their journey to the clinic.

Increasing appointment times would enable more time for patients to complete relevant forms at the start of the appointment, but the amount of time could be reduced (or even eliminated) if we allow them to complete these forms online prior to the appointment, at a time that suits them. Patients who prefer to complete forms when they are at the clinic, or who need assistance in completing the forms, could potentially be advised to arrive 15 minutes early for their appointment to enable this to be done.

Waiting time can also occur between tests during appointments, despite the best efforts of the scheduling system, as sometimes tests take longer than expected, or there is an equipment issue for example.

For complex manufacturing processes there are a number of tools that allow us to identify the bottlenecks in processes, but in my experience, regardless of the industry, the people who work within the process every day know exactly where they occur, and they are usually more than happy to tell you!

They will say things like “it always gets backed up at the xxx test by noon” or “we have to re-boot that piece of equipment 4 times a day which means we lose an hour that we never recover”. People are natural problem solvers, and so the team may have found some creative ways to circumvent these issues, however there are normally a couple of simple steps that we can take to address the root cause of the problem.

–

Take a good, honest look

First of all, a critical, logical examination of how long it actually takes to perform a test might be necessary. If it takes 10 mins to run the test, and 5 mins to clean for the next patient, the test actually takes 15 mins not 10 (no matter what the equipment manual says!), so if we are trying to test more than 4 patients an hour on this piece of kit it won’t happen.

We either need to look at adding another piece of test equipment or reducing the number of tests per hour to resolve this problem.

In-lane retinal imaging, made possible by handheld cameras, is a good example of how practitioners can increase the amount, of patients imaged, whilst reducing bottlenecks caused by limited equipment availability.

If the issue is that only one person in the office knows how to use a certain piece of equipment and, for example, things back-up when they are on their lunch break, this is an easier problem to solve. Cross-training of staff in different processes is a widely used technique in manufacturing which translates well in to a healthcare setting. This means that no matter if someone is on lunch break or vacation, the tests can still be carried out! In my experience people welcome the development opportunity that cross-training offers and are keen to be trained on lots of different equipment types and processes.

Next let’s think about transportation and motion together.

–

Transportation and Motion

In manufacturing, transportation refers to the journey of the part around the shop floor, and motion refers to the technician or operator. So, in a healthcare setting transportation would relate to the patient journey through the clinic, and motion is a relevant consideration for anyone working in the practice.

The importance of uninterrupted FLOW

When looking at the impact of transportation and motion we should ask ourselves if patients move in a predictable sequence along a row of test equipment, or do they move round pieces of equipment or between rooms, only to come back to equipment or rooms they went past? Are you constantly reaching for, or worse, going to track down pieces of equipment that you need to use often?

Initially, reviewing the layout of test equipment alongside the testing sequence(s) can yield some interesting insights. Perhaps the layout is restricted by the placement of power outlets in the clinic, or a seldom used piece of equipment is too heavy to move? Maybe when a new piece of equipment was purchased we didn’t realise how much it would be used and so it was put in an out-of-the way corner? Or maybe it’s just always been like that and we’ve never really thought about it? Whatever the answer is, two things will help to improve flow and therefore efficiency: the first is moving the equipment to match the sequence, and the second is changing the sequence to match the equipment layout. In my experience the answer is normally a bit of both!

What about the equipment you are always reaching for? The answer to that is quite easy – move it closer – however, in practice that can sometimes be difficult. For example, if the power outlet is on the wall and you don’t want cables trailing across the floor, or if the cable is too short, etc, etc. Once again the answer could lie in re-organising your work area, if the equipment can’t come closer to you, can you move closer to the things you reach for the most? Can they be re-organised so that they easy to access?

In addressing transportation and motion wastes the answer will never be perfect as other factors will come in to play (e.g. location of power, water, walls, etc), but you will achieve incremental improvements that all contribute to the overall efficiency and productivity improvements.

–

K.I.S.S – Keeping it Simple

In manufacturing, over-processing refers to the practice of adding more work or higher quality to a product than is necessary to meet customer requirements, and involves unnecessary steps or features that do not add value from the customer’s perspective.

In an optometric practice, the equivalent would be performing extra tasks or procedures that do not add value to the patient’s experience or health outcomes. One example of this could be conducting additional diagnostic tests or screenings that are not clinically indicated or required for the patient’s condition.

Once again, starting with a simple review of what tests are included in each of the different type of exams/appointments can yield some interesting insights. In manufacturing we strive for standardisation or standard work, and these are tools that we use to improve flow, but sometimes this can result in over-processing as our attempts to standardise mean that we incorporate redundant steps. There is therefore a balance to be struck to achieve high levels of standardisation and eliminate over-processing at the same time. In my experience this requires us to establish a sequence of process stages, all of which are required for the most complex product, and a subset of which are required dependant on which product is being manufactured. In an optometric practice the product would be they type of exam (e.g. routine eye exam, diabetic eye exam, contact lens fitting, medical eye exam), and the process stages would be tests such as peripheral vision check, refractive error, retinal image, etc.

–

Who, what, where, and why…?

The key question in this review process is “what proportion of patients need this test?”. If the answer is 100% then this test should be near the start of the sequence, with multiple staff members cross-trained on how to do it, and if the answer is 10% it should be near the end of the sequence and perhaps fewer members of staff need to know how to use this equipment. In manufacturing if it’s not easy to assess whether a part needs a specific test or not, we use a screening test as a method of triaging the parts and determining which test protocol is required.

Talking to the staff members ‘on the front line’ can help you understand exactly what is happening, and what can be done

The same approach can be used in a healthcare setting, and we routinely see triaging in emergency rooms to prioritise the order in which patients see the doctor. A wellness exam (such as a retinal exam taken in the exam lane using the handheld epiCam) can be used to triage patients in an optometric practice to ensure that they are subject to the correct exam-type and are not subject to over-processing when they attend clinic.

When considering over-processing we should ensure that tests are not being unnecessarily repeated, e.g. if the same test is being run on two pieces of test equipment then one of the tests is redundant, and this will be highlighted by a review of the various test sequences.

A review of the manual or with the company website can help to refresh our understanding of the capabilities of all of the pieces of equipment within a practice, as all members of staff may not be aware of all the possible test combinations from all pieces of equipment.

This review could also help to identify a number of pieces of equipment that can run the same test, which could in turn help to alleviate bottlenecks when they occur.

–

Going with the FLOW

As you can see, there are a number of concepts to improve flow, and therefore improve efficiency, productivity and ultimately customer satisfaction, that translate well from manufacturing into a healthcare setting.

I hope you have enjoyed this, and I look forward to sharing more translational insights with you in future.

In the meantime, please let me know of any manufacturing subjects you’re interested in learning more about, as well as any collaborative pieces and white papers you may be interested in contributing to – we love to work with our partners and can’t wait to hear your ideas too!

Speak soon!

Sarah

Sarah Jardine, CEO, epipole